LinkUp Forecasting Net Gain of 210,000 Jobs in May; Greater Job Market Equilibrium Furthers The Soft Landing

LinkUp forecasting fewer job gains than April but slightly above consensus estimates

The week after April’s jobs report came out, the President of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, James Bullard, spoke at the Economic Club of Minnesota. During his remarks, Bullard stated that his base-case scenario for the economy was slowing growth, a somewhat softer labor market, and declining inflation - in other words, the now widely heralded soft landing.

Bullard is hardly alone in his view - the soft-landing scenario that we’ve been vocally and vociforously forecasting for a year has suddenly become the clear consensus view after having been disregarded as delusional even just a few months ago.

Bullard went on to say that “the rumors of the imminent demise of the economy are greatly exaggerated,” pointing to April’s stronger-than-expected jobs report as evidence, after which he recommended to the audience that “maybe you should change your models a little bit.”

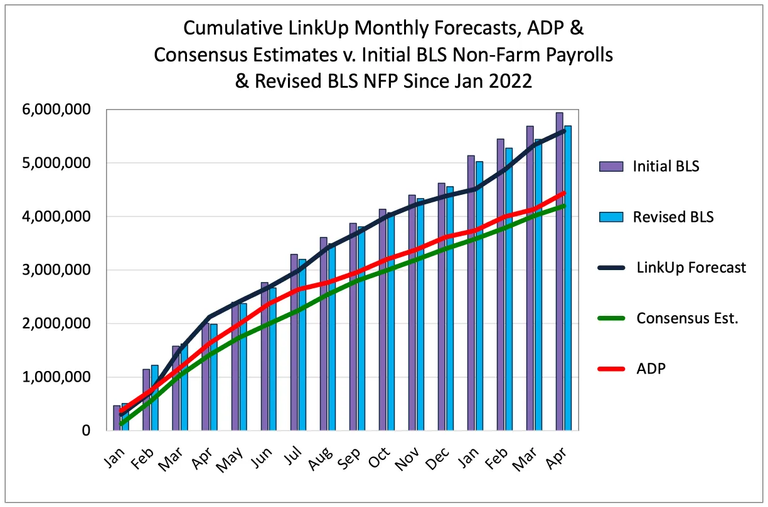

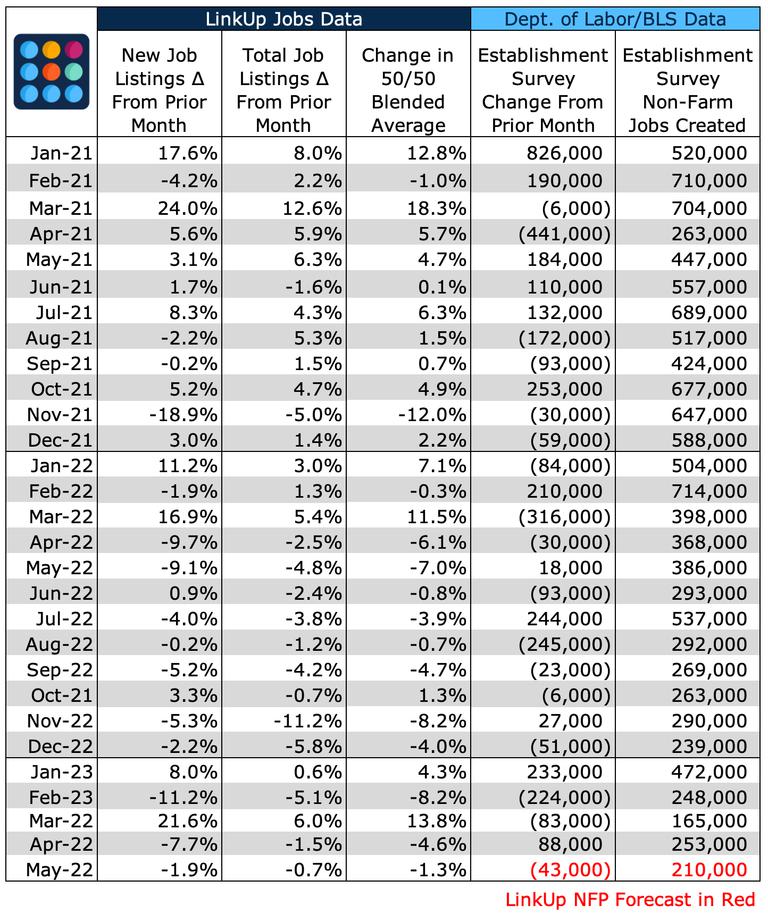

Having missed the April jobs numbers by just 4,000 jobs or a paltry 1.5%, we’re pretty comfortable with our NFP forecasting model. And lest anyone think we’re cherry picking a single month, we’d note that our cumulative forecast since January of 2022 is off from actual by a minuscule 1.8%.

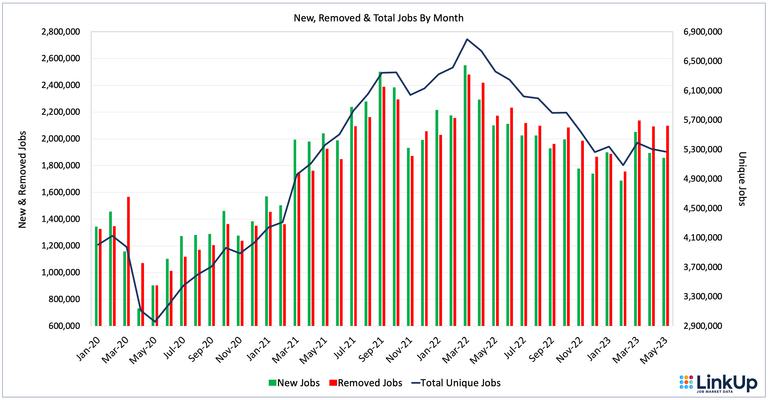

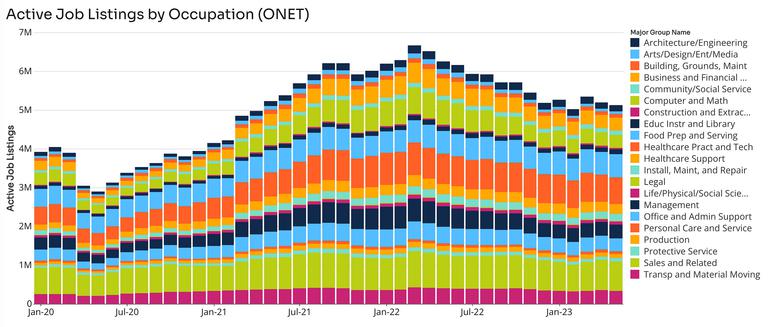

As the chart above indicates, and despite the fact that our job data shows that U.S. job openings indexed directly from company websites globally has dropped 22% since last March, we’ve consistently recognized the strength in the labor market that others have repeatedly underestimated. And it is now that strength that has recently generated much angst and gnashing of teeth about what the Fed might have to do to get inflation under control now that the transitory causes of inflation have subsided (albeit more slowly than most of us expected).

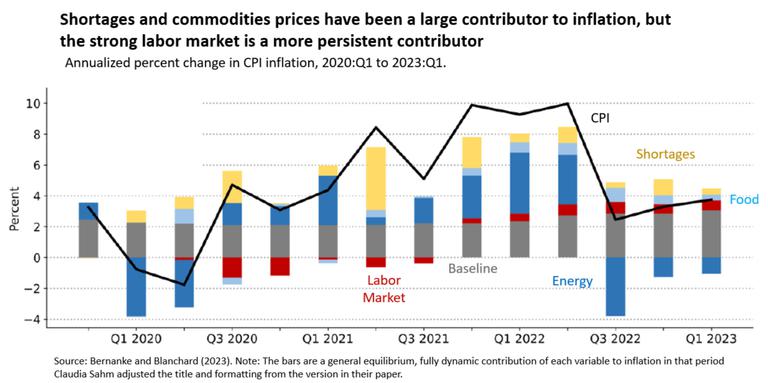

First, regarding those transitory causes of inflation that have dissipated, Ben Bernanke and Olivier Blanchard conclude in a recently published paper entitled ‘What Caused the U.S. Pandemic-Era Inflation?,’ that supply disruptions, commodity price swings, and the war in Ukraine were more significant contributors to inflation than the labor market, and that those issues have largely subsided as indicated by the chart below:

But, the paper also concludes that the labor market has stood and will likely continue to stand as the most persistent contributor to inflation going forward. As Claudia Sahm perfectly summarizes:

Bernanke and Blanchard argue that supply disruptions and commodity price swings due to Covid and especially the war in Ukraine have contributed substantially to inflation. The strong labor market and the extra demand for goods that were often in short supply led to inflation, too. Both inflation optimists and inflation pessimists were right and wrong about inflation in different ways. It’s complicated. The question now is how much the labor market (and the demand supports) continues to push up inflation.

As we’ve been saying over a decade (with some bias, of course), the job market is the only thing that matters - the rest is noise. And on that front, a few charts are worth noting before we turn to what we’re seeing in the LinkUp data.

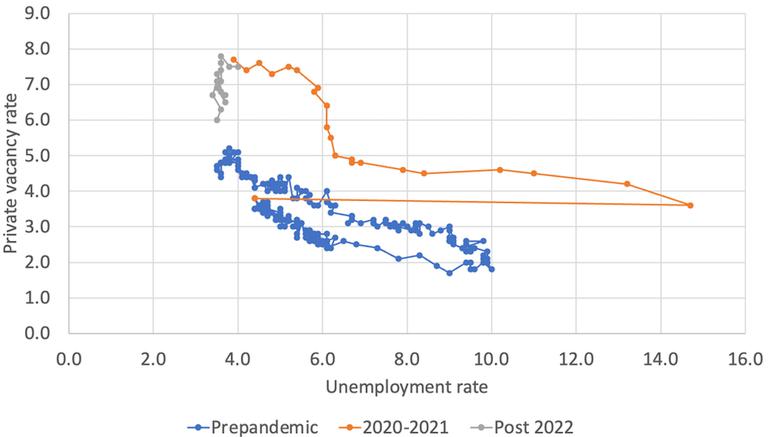

As the Beveridge curve indicates (in gray), vacancy rates (which can be simplified down to basically being considered a measure of labor demand as measured by job openings) have dropped considerably over the past 16 months without having induced any uptick in unemployment.

But as Sahm (later in the same article mentioned above and also citing Mui) and Krugman and Goldman Sachs have all recently pointed out, job openings estimates generated by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) as part of their JOLTS release are highly suspect and have become even less reliable and arguably more irrelevant in the pandemic era due to how lagged the data is (not to mention the availability of more accurate and timely job openings data provided by LinkUp).

Having said that, however, the data we collect directly from tens of thousands of employer websites across the U.S. and around the world shows a very similar 20-25% drop in labor demand across the U.S. economy as nearly all of the LinkUp charts below indicate. Labor demand across the U.S. has most definitely been dropping steadily since last March.

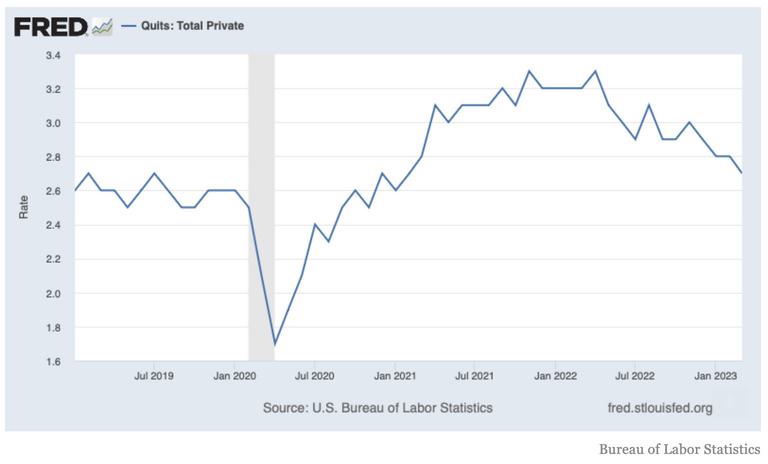

And quit rates have been dropping steadily as well and are now approaching pre-pandemic levels, a strong indication that the job market has reached or is very close to reaching equilibrium between labor demand and supply.

Of course, pockets of imbalance will likely persist indefinitely in sectors such as leisure and hospitality, food service, retail, etc. but across the entire economy, the job market has performed precisely as we thought it would when we started forecasting the soft landing over a year ago. And we expect that that performance will continue tomorrow with May’s jobs report, when we anticipate that the Employment Situation Report for May will show a net gain of 210,000 jobs for the month.

Looking at our data for May, total job openings in the U.S. fell 0.7%, new openings dropped 1.9%, and job openings removed from company websites fell 0.3%.

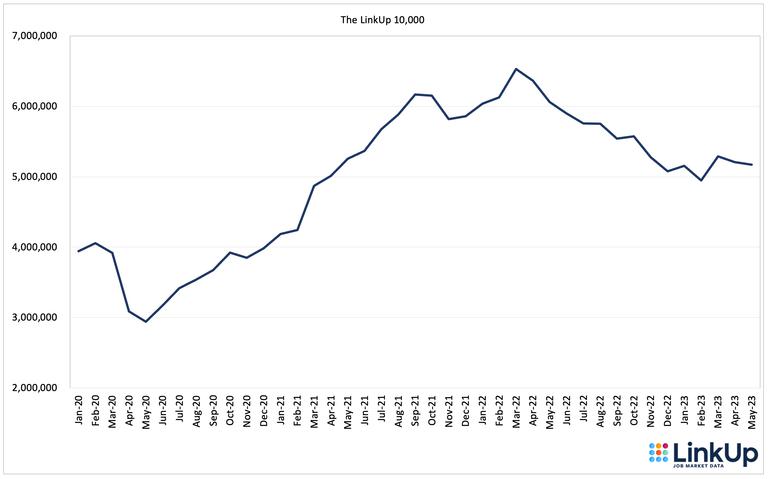

The LinkUp 10,000, which tracks U.S. job openings for the 10,000 global companies with the most openings in the U.S., also fell 0.7%.

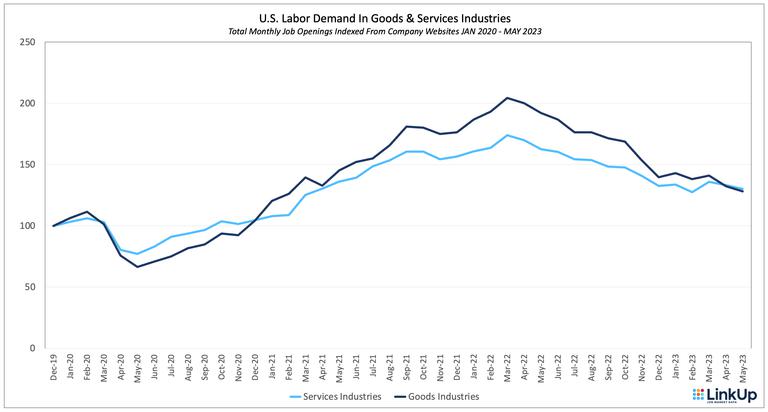

Job openings declined in both manufacturing and service industries and are now both roughly 30% above where they stood just before the pandemic hit.

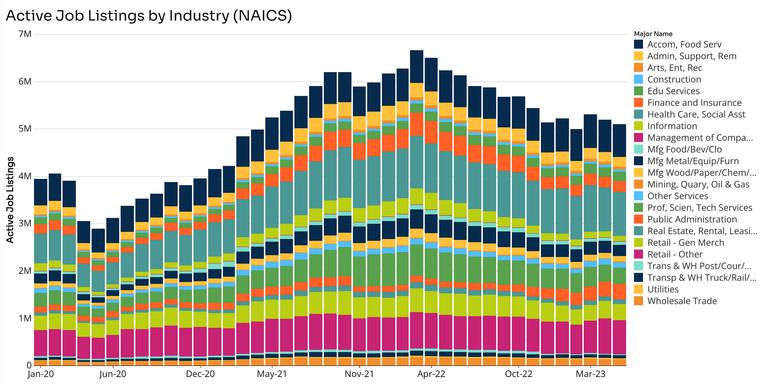

By industry, openings rose the most in Retail and dropped the most in Professional Services, Technology, and Manufacturing.

By occupation, openings rose the most in Transportation, Personal Care, and Sales and dropped the most in Business & Finance, Arts, Media & Entertainment, and Physical and Life Sciences.

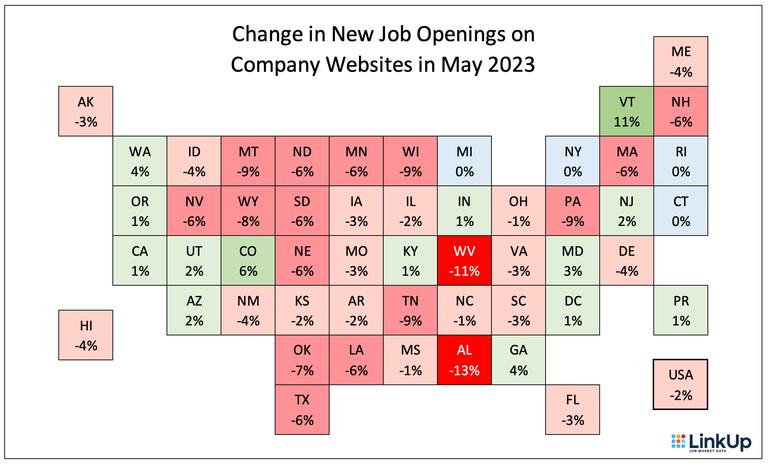

Across the country, new openings dropped by 2% with only 14 states showing an increase and 4 with 0% change.

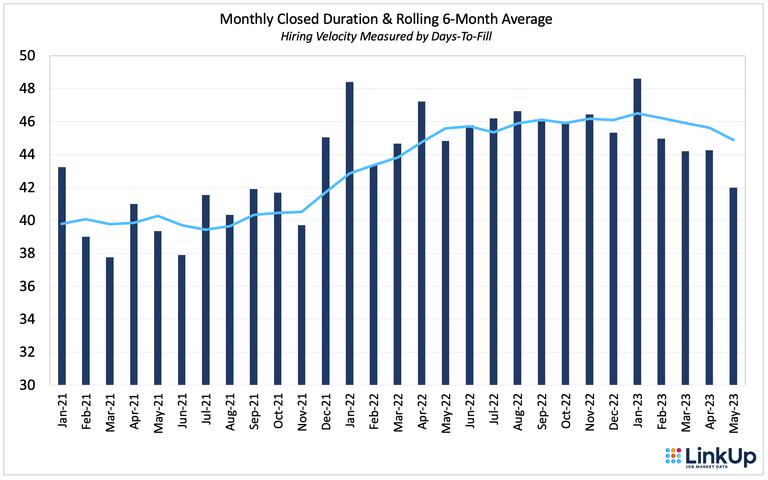

Across the entire economy, it took an average of 42 days for employers to fill openings in April - the long-term historical average ‘time-to-fill.’ With May’s duration data, the rolling 6-month average Closed Duration stands at 45 days, precisely the average hiring velocity for employers across the U.S. over the past decade, providing further evidence that the job market has achieved a high degree of equilibrium.

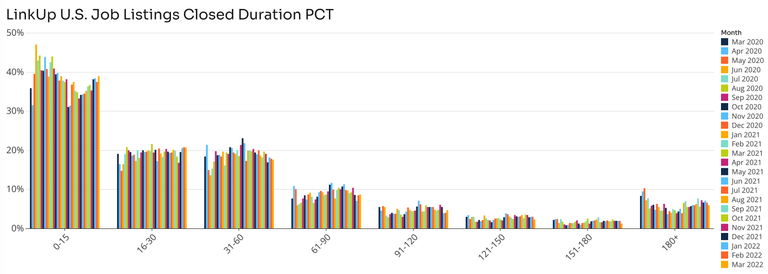

As we wrote in a piece a few weeks ago about the myth of so-called ‘ghost’ jobs, we also break down our duration data by various duration ranges to track what’s driving duration as a whole, and the noteworthy jump over the past few months in jobs that were removed after only having been posted for less than 30 days continued in May.

So based on job openings data for April, we are forecasting a net gain of 210,000 jobs in May, a drop from April but slightly above the 195,000 consensus estimates.

Let the soft landing continue!

Insights: Related insights and resources

-

Blog

05.10.2023

LinkUp's April 2023 JOLTS Forecast

Read full article -

Blog

05.04.2023

April 2023 Jobs Recap: Labor demand declines across most industries and occupations

Read full article -

Blog

05.02.2023

LinkUp Forecasting Net Gain of 260,000 Jobs in April as Job Market Remains Resilient

Read full article

Stay Informed: Get monthly job market insights delivered right to your inbox.

Thank you for your message!

The LinkUp team will be in touch shortly.